Knowledge

ConvivialCNC is the result of a master thesis in architecture under the title: “Convivial Numerical Architecture – Convivial Technology for Building in Existing Contexts”. If you are interested in wood as a material, the psychology of do-it-yourself, sustainable (architectural) production, CNC technology or digital planning and production, the following summary will surely be interesting for you! The focus is on architecture, but most of it can also be applied to production in general. The sources are always listed at the bottom of each topic. Since the thesis was originally written in German, some (not all) of the sources are written in German as well.

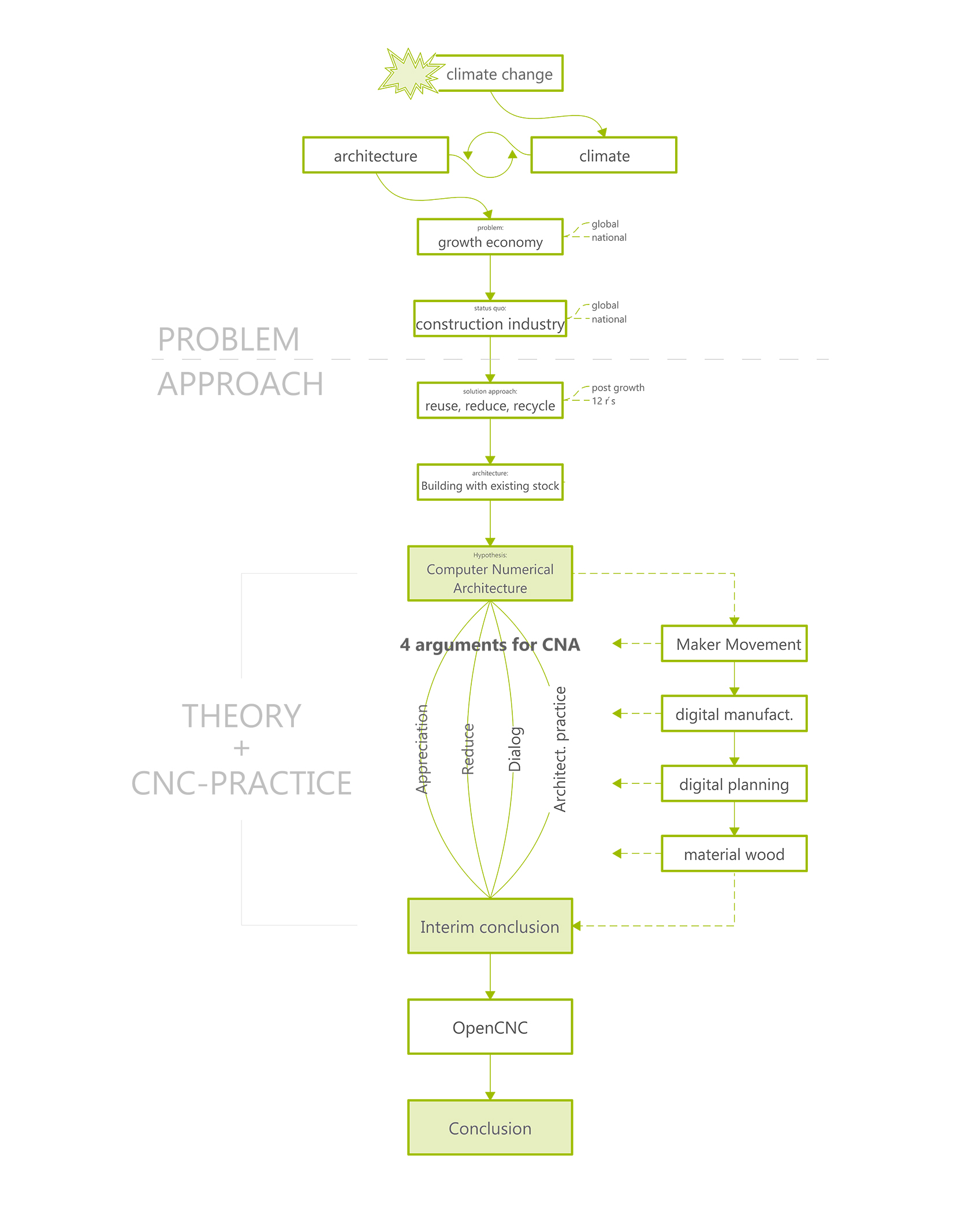

To clarify the thesis´ structure, you can find a graphical table of contents in the following:

Climate Crisis

The starting point and argumentative basis of the thesis is the impending climate catastrophe. Our earth is warming up, mainly due to mankind and its greenhouse gas emissions (1). The temperature change has serious consequences for the ecosystems on the whole planet, especially if so-called tipping points are reached, which mean irreversible changes. The fact that we could reach some of the predicted tipping points before the end of this century (2) proves the urgency of bold action and global political, economic, and societal rethinking. Civil society – that is, you and me – has a crucial role to play, as politics and economics can only ever echo general lifestyles and culture. So, it is time for US to act!

Sources:

(1) Umweltbundesamt (UBA), 2016: Klimawandel. [Online] https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/themen/klima-energie/klimawandel (06.05.2021).

(2) Umweltbundesamt (UBA): Kipp-Punkte im Klimasystem. Welche Gefahren drohen?. Dessau-Roßlau: Umweltbundesamt, 2008. Umweltbundesamt (UBA), 2010: Rohstoffeffizienz – Wirtschaft entlasten, Umwelt schonen. [Online] https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/publikation/long/4038. pdf (22.05.2021).

ARCHITECTURE AND CLIMATE/ GLOBAL CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY

The climate determines how buildings are constructed – and how buildings are constructed has an impact on the climate. The knowledge of this has been around for a long time. And yet many people are not aware of the decisive influence the building sector has on greenhouse gas emissions: in 2020, it will account for 38% (!) globally (1). Furthermore, demolition, disposal and new construction of buildings generate 52% (!!) of the total national waste in Germany, for example (2). A figure like this is not easily transferable to other countries, yet it illustrates what our dwellings and the way we build and inhabit them can do.

The global construction industry is responding to such figures and political pressure with “sustainable” products – such as passive, zero, or plus-energy houses. At first glance, this is a positive development, but unfortunately, according to a UN report, these efforts are not enough – on the contrary, they are actually declining, so that we are moving further and further away from the 1.5° target defined in the Paris Agreement (3).

Sources:

(1) United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): 2020 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction. Towards a zeroemissions, effi cient and resilient buildings and construction sector. Nairobi, 2020.

(2) Braun, Steff en; Rieck, Alexander; Bullinger, Sebastian; KöhlerHamemer, Carmen; Walz, Arnold; Bauer, Wilhelm: FUCON 4.0 – Nachhaltiges Bauen durch digitale und parametrische Fertigung. Projektbericht. Stuttgart: Fraunhofer IRB Verlag, 2019.

(3) United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): 2020 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction. Towards a zeroemissions, effi cient and resilient buildings and construction sector. Nairobi, 2020.

GROWTH

One possible explanation for this damaging trend could be the financial growth imperative under which all actors act. For decades, the paradigm of economic growth, measured by GDP, has prevailed almost all over the world. However, it has been proven that an ever increasing humanity with ever increasing demands will and is already pushing the limits of the planet (1). This can be related, for example, to the available resources. Or also to increasing greenhouse gas emissions, in which the global world economy has a massive share (2). The pressure for growth often leads to aspects such as sustainability and quality taking a back seat to profit interests. This leads to our current consumption consuming far more resources than our planet can supply (Earth Overshoot Day). This contradicts all principles of sustainability and already leads to huge environmental damage, with which social problems are also linked, especially in the global south.

Sources:

(1) Trainer, Ted: Renewable Energy Cannot Sustain a Consumer Society. Dordrecht: Springer, 2010.

(2) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): Zusammenfassung für politische Entscheidungsträger. In: Klimaänderung 2014: Minderung des Klimawandels. Beitrag der Arbeitsgruppe III zum Fünften Sachstandsbericht des Zwischenstaatlichen Ausschusses für Klimaänderungen. Cambridge, Großbritannien und New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press, 2015. Deutsche Übersetzung durch Deutsche IPCC-Koordinierungsstelle, Österreichisches Umweltbundesamt, ProClim, Bonn/Wien/Bern, 2015.

Reduce / Reuse / Recycle

It seems that alternative models of life, society and economy are needed to save our planet and thus the survivability of our species. But how can something like this look like?

One answer to this question could be post-growth economics (degrowth), which assumes that decoupling economic growth and environmental degradation is not possible (fast enough) and therefore designs a society that is frugal and partially self-sustaining (1). Post-growth economists like Serge Latouche bring into play terms like reevaluation, reconceptualization, restructuring, redistribution, relocalization, reduction and recycling – summarized under the three generic terms Reduce / Reuse / Recycle, a strategy from waste management is applied here to a new kind of production that can lead to a sustainable future. The core of this strategy is to avoid consumption by consistently questioning, repairing and exchanging – and only reaching for a new product if there is no other way. This attitude can easily be applied to the production of architecture, which suggests a consideration of the existing.

Sources:

(1) Paech, Niko: Befreiung vom Überfl uss. Auf dem Weg in die Postwachstumsökonomie. München: oekom Verlag, 2012.

EXISTING BUILDINGS (+ GOODS)

Existing products – including buildings – are tied-up resources and usually caused environmental damage during their production due to resource extraction, manufacturing energy, transportation energy, etc. Far too often, products are discarded and buildings demolished for economic reasons, even though they would still have been usable or repairable. The production of new products then leads to renewed resource and energy consumption. For example, renovating a massive building can reduce the use of abiotic materials from 5,000 kg/m² to 1,000 kg/m² compared to new construction. (1) These saved materials no longer have to be extracted, processed and transported – at the same time, comparable energy standards, e.g. of the building envelope, can be achieved.

Furthermore, not only valuable resources and “grey energies” are lost with a new acquisition, but often also cultural values, such as traditions or memories. Often existing objects possess characteristics of another time, tell stories or show masterful craftsmanship, which are irretrievably lost with a disposal.

Besides the seemingly higher costs, especially in the area of buildings, risks that are difficult to calculate, legal requirements, a lack of awareness and a lack of training of the planners are reasons for premature disposal. In today’s economic framework, further privileging of the new remains likely.

Sources:

(1) Wallbaum, Holger; Kummer, Nicole: Entwicklung einer HotSpot-Analyse zur Identifi zierung der Ressourcenintensitäten in Produktketten und ihre exemplarische Anwendung. Wuppertal: Wuppertal Institut für Klima, Umwelt und Energie, 2006.

INTERIMS CONCLUSION - COMPUTER NUMERICAL ARCHITECTURE (CNA)

It has become clear that the approaching climate catastrophe obliges each individual to question his or her own consumption behavior, since not enough is being done by the established players in politics, business, etc. The following section shows that a change in consumption behavior does not necessarily have to go hand in hand with a negative renunciation.

In this interim conclusion, the thesis is put forward that digital planning and manufacturing methods in broad mass application can trigger a socio-ecological transformation towards a self-evident and climatefriendly utilization of existing (building) substance. The basis for this thesis is, among other things, the recent strong increase in accessibility to CNC systems through projects such as the Maker Made M2, Goliath CNC or the Shaper Origin, which are characterized by intuitive use, large machining areas and the high potential for linking to the ecological material wood, even for laypersons.

Below, we put this thesis through its paces and elaborate on what digital design and manufacturing mean, what the Maker Movement has to do with it, and why wood as a material plays a crucial role.

MAKER MOVEMENT

The first argumentative building block and target group for the previously introduced novel CNC milling machines are Makers all over the world. These people, who get down to work and, through creativity and dedication, create individualized products that are not available for purchase, have already initiated the next industrial revolution – Mass Customization (1). This is occurring as a deliberate counter to mass production. One of the main drivers for this is still the 3D printer – CNC milling offers the great potential to take the movement to the next level.

The Maker Movement as a long-lasting and growing bottom-up revolution shows (2) that more and more people long for an alternative to mass production and mass consumption and are also willing to spend time, energy and financial resources on this new lifestyle. The extent to which the Maker Movement is in line with sustainability goals will be shown later. For a better understanding of the movement, the Maker Movement Manifesto by Mark Hatch is recommended as a starting point (3).

(1 + 2) Millard, Jeremy; Sorivelle, Marie N.; Deljanin, Sarah; Unterfrauner, Elisabeth; Voigt, Christian: Is the Maker Movement Contributing to Sustainability?. Basel: MDPI, 2018. [Online] https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072212

(3) Hatch, Mark: The maker movement manifesto: rules for innovation in the new world of crafters, hackers and tinkerers. McGrawHill Education, 2013.

DIGITAL MANUFACTURING

Digital manufacturing generally means the computer-controlled creation of physical objects based on digital data and information. The comparatively seamless interface between digital planning and manufacturing makes it possible to produce even prototypes, one-offs, and very small series economically (1).

A prominent example of this type of manufacturing is the additive process of 3D printing, which has also become widespread in the private sector. However, despite many further developments, this remains smallscale with few exceptions. Furthermore, the materials that can be used are limited – these are often plastics, synthetic resins or, in the construction industry, concrete and, more recently, clay. The trend towards 3D printing of houses must therefore (still) be viewed critically, since it is primarily unecological concrete that is used, and it is primarily a further increase in the efficiency of the construction process in economic terms.

Subtractive processes, in particular CNC manufacturing, are more promising here. This is mainly due to the materials that can be used, such as plastics, metals, mineral materials and especially wood. In addition to ecological advantages, which will be discussed later, wood offers positive characteristics regarding the potential for connection for laypersons and local availability around the world – perfect conditions for a socio-ecological bottom-up transformation.

(1) Dunn, Nick: Digital Fabrication in Architecture. 1. Auflage. London: Laurence King, 2012.

CNC Manufacturing

“CNC” means “Computer Numerical Control,” which is the computer-controlled process of machines, and thus is a process of digital manufacturing. A CNC mill cuts a material under numerical control by moving a rotating cutting tool (the cutter or milling head) through the material with the help of electric motors.

The first purely numerical control of a machine was developed in 1805 by Frenchman Joseph Marie Jacquard in the form of a loom to compete with the low-priced woven products of the English. Until the 1980s, machines based on this idea were controlled by punched cards (1). The first truly computer-controlled machine was developed in 1952 by engineers John T. Parsons and Frank L. Stulen, in collaboration with IBM and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, to precisely manufacture military helicopter rotor blades. (2) Space and aerospace drive the technology several times from then on – for example, the first computer aided design (CAD) program called CATIA is also developed by the aerospace company Avions Marcel Dassault (3).

Milling can also be done manually or mechanically, but CNC control allows for greater precision, speed, and repeatability. Most CNC milling machines work horizontally with three, five or more axes controlled by GCODE (more about the structure and commands here). The Maker Made M2 used for ConvivialCNC is an exception here, as the milling head moves almost vertically suspended from chains. Both types of structure generally assume flat materials, such as sheet materials. Milling parameters that affect the quality and time required for a milling operation can be the material used, the type and size of the cutter used, the rotational speed of the cutter, the feed rate, the milling depth per pass (= infeed), and so on. Finding the optimum interplay of these parameters requires experience and practice – and can best be tried out on the milling machine itself, observing a few rules of thumb and safety aspects! These are roughly summarized:

01) do not go deeper than half the diameter of the cutter per pass.

02) sharp cutters are important because they improve the milling result and reduce the temperature development on the workpiece.

03) the slower the cutter moves forward; the more friction is created in the same place and the temperature of the cutter/workpiece increases. This can damage the cutter and in the worst case lead to fire development….

04) …for this reason, a milling operation must never run unattended and adequate precautions against fire must always be taken. For example, a fire extinguisher should always be at hand.

05) A further risk reduction is consistent extraction of chips and dust produced during milling. This is because a milling cutter that is as free as possible rubs less and can be cooled by the surrounding air. In addition, extraction can minimize the inhalation of milling dust, which is good for the user’s health.

06) The Maker Made M2 has special features that need to be considered. For more info, check out the Maker Made webpage or the very active Facebook group “MakerMade Owners”.

(1+2+3) Pfeiffer, Sven: Digital Manufacturing. Overview. In: Atlas of Digital Architecture. Terminology, Concepts, Methods, Tools, Examples, Phenomena. Hrsg. von Hovestadt, Ludger; Hirschberg, Urs; Fritz, Oliver. Basel: Birkhäuser, 2020. S. 405-420.

Digital Planning

Digital manufacturing has enormous potential when combined with smart digital planning tools. The subject area is very complex and multi-layered, which is why the following section primarily provides an overview of useful software and databases for laypersons.

Those who do not yet dare to create their own designs or do not have the time to familiarize themselves with the relevant software can make use of databases/libraries that offer (almost) ready-made CAD (computer-aided design) files for download, which then only have to be prepared in CAM (computer-aided manufacturing) software for processing with the CNC. In the field of 3D printing, Thingiverse.com is very well known. For CNC milling, there aren’t as extensive databases (yet), but again, there are incredibly cool sources that offer everything from furniture to houses.

For example, OpenDesk offers free high-quality designer office furniture for home use that can be made entirely using CNC milling.

Like Thingiverse, Grabcad and Sketchup’s 3D Warehouse, for example, provide large databases of 3D models, some of which can be used for CNC milling. Open Systems Lab offers with Wikihouse and BuildX the possibility to download production files for whole houses. Especially in the UK and the Netherlands there are some impressive, realized examples. If a custom design is to be created and produced, there is no getting around computer-aided drafting.

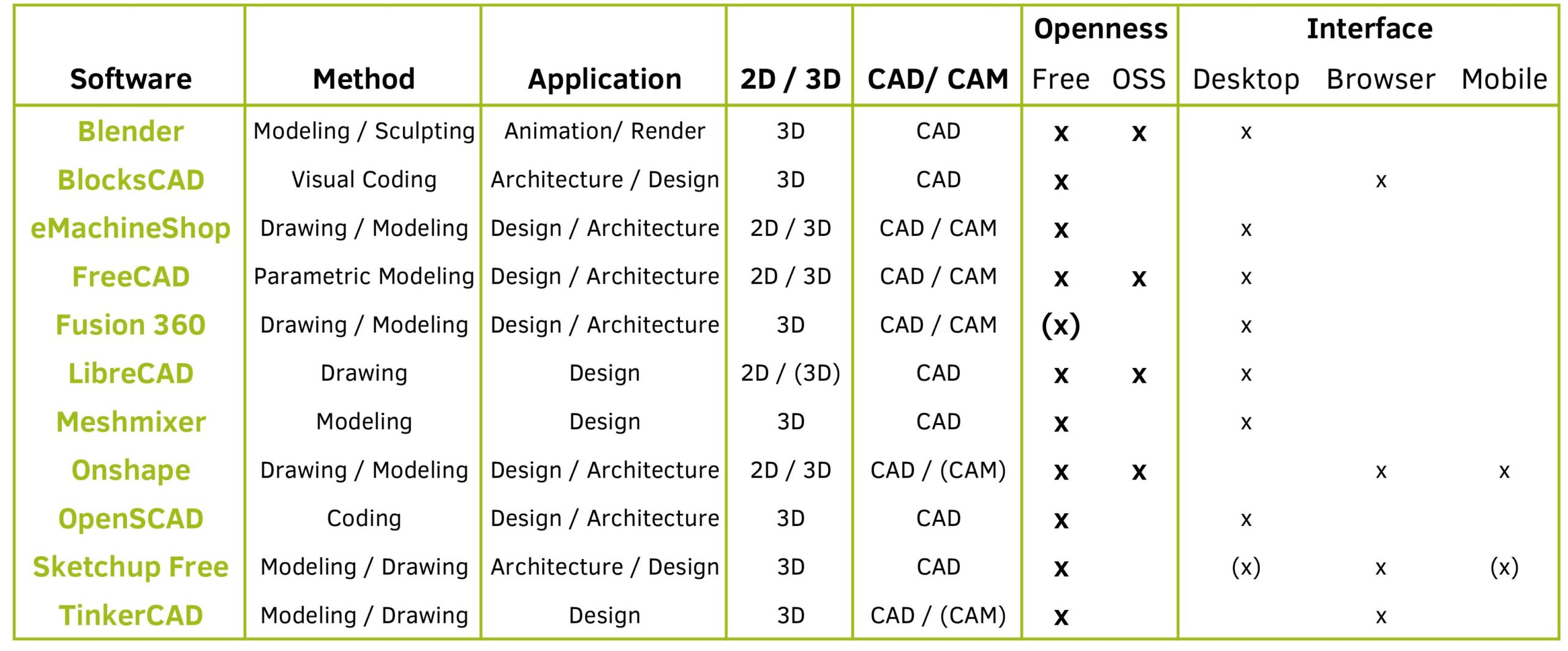

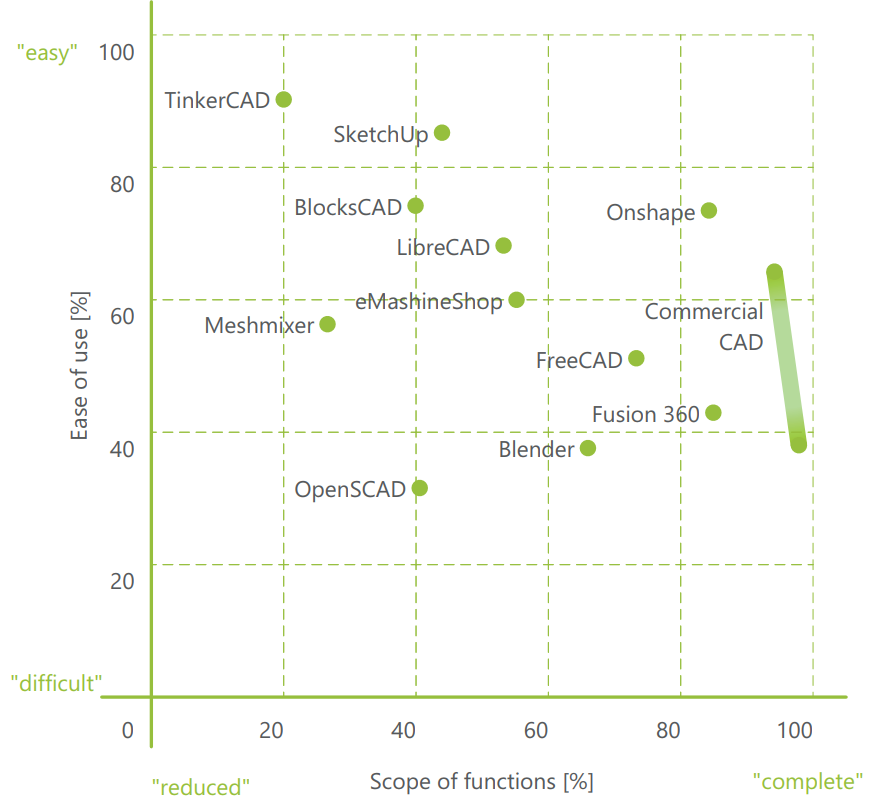

Professional CAD and CAM applications can quickly become very complex but offer a wealth of helpful functions that make even the most complex tasks feasible. For most projects, however, basic functions are sufficient, even in the professional field. Fortunately for all makers, there are several free CAD and CAM programs that cover a broad spectrum in terms of user-friendliness and functionality. Thus, there is exactly the right application for everyone – the only difficulty is finding it. For this reason, the following graphic gives an excerpt-like overview of some offers on the Internet.

(Graphic based on: Junk, Stefan; Kuen, Christian: Review of Open Source and Freeware CAD Systems for Use with 3D-Printing. In: Procedia CIRP

50. 50. Ausgabe. Hrsg. von Elsevier B.V.. Amsterdam: Elsevier B.V 2016. S. 430-435 [Online] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2016.04.174.)

If an existing object is to be processed/ supplemented/ adapted, 3D scanning can become interesting. For this purpose, the so-called photogrammetry is especially suitable for laymen, since it can lead to useful results even with a normal smartphone camera. A good overview of the options can be found here.

And of course, CAM software should not be missing in this section, which converts CAD drawings into machine-readable codes and is thus essential for CNC milling. Here, too, there are free offerings such as Fusion 360, OpenBuilds CAM, Estlcam, FreeMill, DXF2Gcode and Easel. These programs also differ greatly in the number of functions and complexity – Easel is a very intuitive entry-level program, after some time, Fusion 360, for example, could become interesting with infinite setting options and parameters.

For all previously described software options applies information and tutorial platforms such as YouTube, Instructables or Openbuilds can be incredibly helpful if you are faced with a seemingly unsolvable problem – for almost everything there is the right solution on the Internet or the appropriate beginner video.

Regarding the Maker Made M2, in addition to the “Maker Made Owners” Facebook group, the following YouTube channels and videos are recommended: Tim Sway, RobtheBuilder and Commando Designs.

WOOD AS MATERIAL

Wood became a resource for humans early on due to its widespread use and ease of processing. Over the millennia, impressive processing practices of the material developed. Unfortunately, much of the knowledge built up has been forgotten with the onset of industrialization in the 19th century. In recent years, however, wood as a material has been gaining increasing attention in the building industry in view of climate targets (1).

Due to its naturalness, wood has unique properties compared to steel, concrete and plastic. Thus, each piece is unique, shaped by its growth parameters. This can mean advantages and disadvantages for its use as a building material.

Of great value to the ecology of the material is that the mass of a tree consists of CO2 sequestered during growth. If we harvest the wood and then use it instead of letting it rot, the greenhouse gas remains bound and is thus removed from the atmosphere in the medium to long term. In addition, wood replaces other materials, most of which actually release considerable amounts of greenhouse gases during their production instead of binding them. Another advantage is that wood has an optimum balance between stability and lightness. This brings advantages, for example, in architectural projects, but also means that it is easy to work with and is easy on the back. In general, wood can be shaped even with simple tools, which makes it an ideal material for makers.

The naturalness also has advantages in terms of the spatial effect of wood because the look and feel of the material can have positive properties on the health and psyche of people (2). Furthermore, it provides a good indoor climate, as it has a regulating effect on e.g., air humidity, and has a relatively good heat insulating effect due to the high air content.

A disadvantage is that wood reacts sensitively and unevenly to changing ambient humidity due to the tubular cells that run parallel to the direction of the trunk. When wood becomes moist, its volume increases (swelling); when it dries, its volume decreases (shrinkage). The degree of change depends on the relation to the fiber direction and the degree of moisture change. The consequences of swelling and shrinkage can be effectively reduced by installing wood products with the correct moisture content (close to the ambient moisture content) and protecting them from moisture, for example. This also protects against fungal and insect attack. Panel materials often used in CNC machining (e.g., birch multiplex) are made of cross-twisted layers and thus significantly reduce swelling and shrinkage, as the directions “lock” each other (plywood). When used correctly, the disadvantages can therefore be reduced to such an extent that wood presents itself as a material with excellent properties.

Wood has a bad reputation in terms of fire hazard. This could be due to simple everyday experience that wood burns, or to well-known negative historical examples. But as is so often the case with prejudices, these are only partially true. It is true that wood is indeed a combustible material, but in terms of building with wood, it has been shown that wooden structures are in no way bad when properly executed. This is due to a layer of charcoal that, for example, wooden beams form when flamed. This layer has a heat-insulating effect and protects the core, which remains load-bearing for a long time. Thus, a wooden structure can be more stable than, for example, one made of steel, whose strength suddenly decreases sharply from a temperature of about 400°C (3).

As the sharp price increase in Europe of up to 100% in 2021 has shown, wood is now also subject to the complex mechanisms of the global market (4). But it is in local availability that there is great potential for cost and transport reduction, with associated greenhouse gas emission savings. Thus, whenever possible, local wood should be used for projects of all kinds.

(1) Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis): Bauen und Wohnen. Baugenehmigungen von Wohn- und Nichtwohngebäuden nach überwiegend verwendetem Baustoff Lange Reihen z. T. ab 1980. 2020. Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis), 2021. [Online] https:// www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Branchen-Unternehmen/Bauen/Publikationen/Downloads-Bautaetigkeit/baugenehmigungenbaustoff -pdf-5311107.pdf?__blob=publicationFile.

(2) Ikei, Harumi; Song, Chorong; Miyazaki, Yoshifumi: Physiological effects of wood on humans: a review. In: Journal of Wood Science . Bd. 63, Nummer 1. Japan: Springer Science + Business Media, 2017. S.1–23.

(3) Neuhaus, Helmuth: Ingenieurholzbau: Grundlagen – Bemessung – Nachweise – Beispiele. 4. Aufl age. Wiesbaden: Springer Vieweg, 2017

(4) https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1238743/umfrage/preisentwicklung-der-erzeugerpreise-fuer-holz/

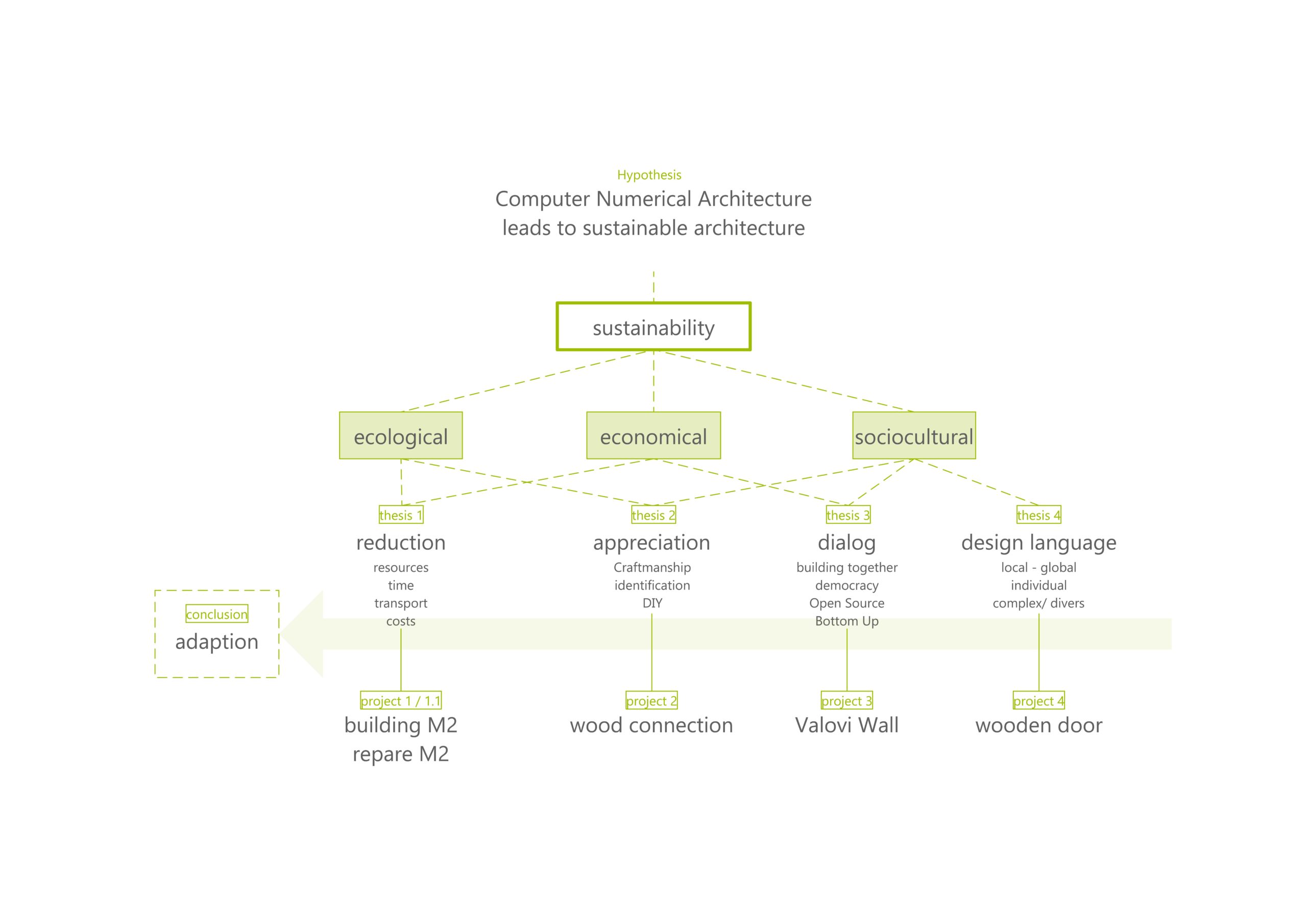

Interims Conclusion 2 - Four arguments for CNA

In the following, four theses are put forward, which result from the background knowledge gained and which will be worked on theoretically and practically in the following:

01. computer numerical architecture leads to sufficiency resp. reduction

02. computer numerical architecture increases the appreciation for the built environment and products

03. computer numerical architecture promotes communities on local and global level

04. computer numerical architecture leads to a new practice of architecture and production

The four theses culminate in the assumption that CNA can initiate the much-needed socio-environmental turn towards a self-evident and sustainable utilization of the existing. For this, the three pillars of sustainability – ecology, economy, and socio-culture – are of crucial importance. The four theories will now be explained in more detail and each of them will be demonstrated in the practical experiment on the M2.

THESIS 1 - SUFFICIENCY / REDUCTION

The core of the thesis formulated here is that CNA, in accordance with the principles of post-growth economics and the 3 R’s (Reduce, Reuse, Recycle), leads to reduced construction and production practices and consequent reduced costs, timescales, risks and resource consumption.

Costs can be reduced by producing simple, replicable solutions and products adapted to individual needs by non-experts. The decoupling of economic pressure enables step-by-step, optimizing production that is freed from profit constraints. Above all, the compensation of financial costs through personal time commitment is important. Of course, this requires a certain amount of motivation, know-how and time – here, for example, ConvivialCNC can help to increase the share of personal effort. If many people with a similar mindset work on everyday problems, it is still likely that innovations will be shared and processes can thus be further optimized.

Time can be saved especially with local production. Depending on the transport distance of raw materials and products and their availability on the market, delivery times can sometimes be very long (see, for example, Wood Shortage 2021 in Europe) . Here, the use of local products or the reuse of existing resources can lead to a much faster result and also be resource-saving. Furthermore, production steps can also be outsourced with the help of local FabLabs, for example, in order to accelerate processes.

This thesis was also proven in the first practical project, in which damage to the ring of the Maker Made M2 was repaired comparatively in three ways: 1.) ordering spare parts, 2.) local remanufacturing in a neighboring metalworking company, and 3.) simple manual repair. All three ways resulted in a mill that was functional again – but way 1 took about 3 weeks, while way 3 took only a few hours and produced spectacular photos to boot:

THESIS 2 - APPRECIATION

The core of the thesis formulated here is that DIY increases the appreciation and respect for products and, as a result, new products are purchased less frequently. This reduces resource consumption and preserves old values. In addition, the Makers have personal advantages by making things themselves.

An important keyword here is participation, i.e. sharing in the creation process. Michael I. Norton’s research on the so-called “Ikea effect” proves that appreciation increases significantly when people make something themselves (1). In addition, working by hand can have other positive consequences for the Maker, such as pride in the work done, fertilized thought processes between hand and brain, sense-making, autonomy, increased well-being, and mental health (2, 3). This can be further enhanced if the results of the work are shared with other makers on the Internet, for example (4). It would be desirable that the practical work thus also becomes more appreciated again in the professional and academic context and is subsequently also aligned again in terms of financial remuneration.

However, it must also be made clear that the previously described aspects of practical work only occur if the work produces a positive result. In case of failure, the right mindset is crucial here – mistakes and problems should be understood as challenges, the overcoming of which makes people all the happier later on. The right mindset is also important for overcoming oneself in the first place and getting started with craft work. It is important to prevent the individual from being overwhelmed – this is where ConvivialCNC can help, among other things, as it is a low-threshold offering that breaks down barriers to entry.

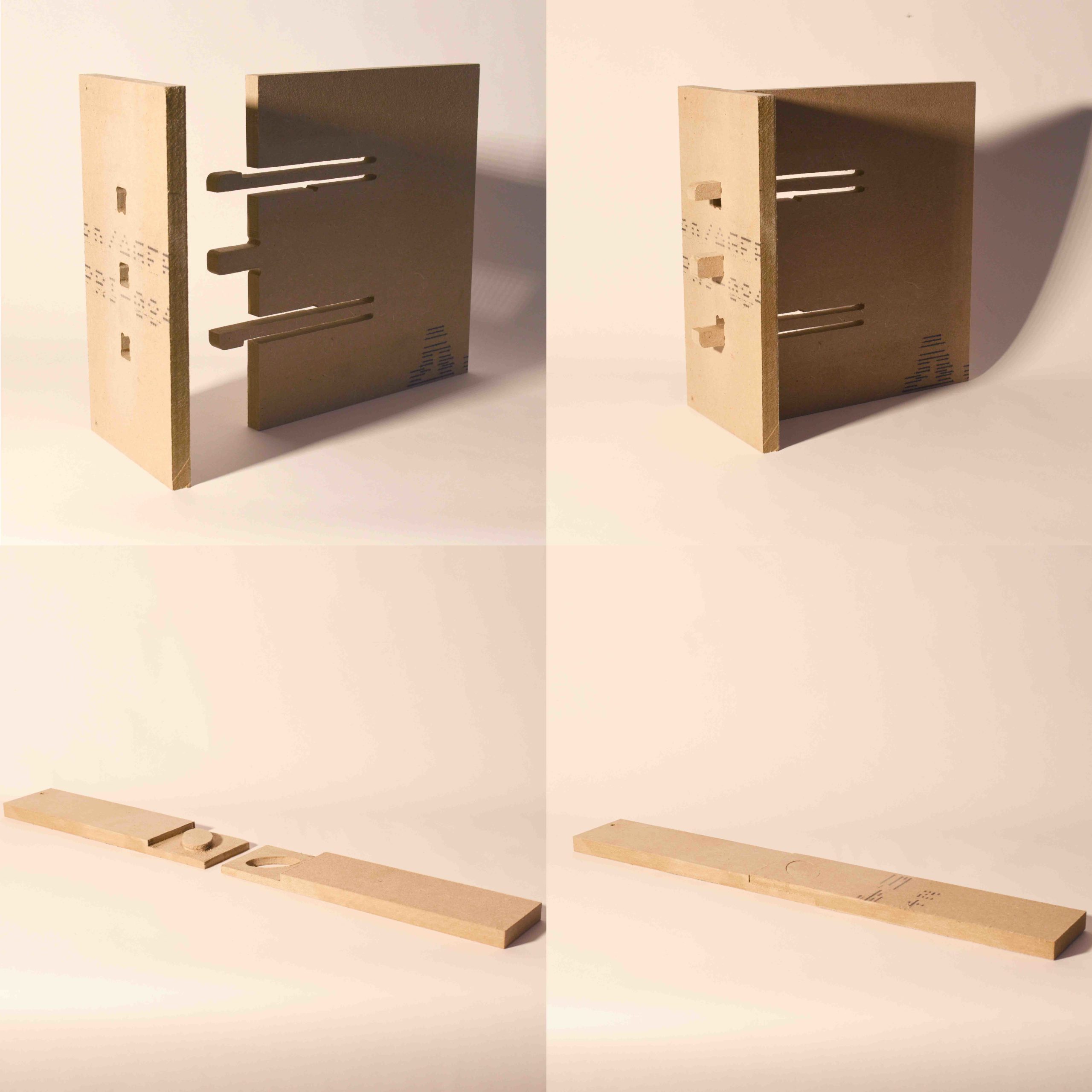

Based on impressive historical Japanese and European woodwork, traditional wood joints were examined for the second practical project and subsequently transferred to digital production. At the same time, this was an experiment in the accuracy of the M2 in the production of joints:

(1) Norton, Michael; Mochon, Daniel; Ariely, Dan: The IKEA effect: When labor leads to love. Elsevier BV, 2012. [Online] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2011.08.002.

(2 + 3) Sennett, Richard: Handwerk. Berlin: Berlin Verlag, 2008.

(4) Sennett, Richard: Zusammenarbeit. Was unsere Gesellschaft zusammenhält. Berlin: Hanser, 2012.

These 3 - Dialoug

The core of the thesis formulated here is that CNA can lead to an increased exchange on a local and global level, which leads to an enrichment, dissemination and emergence of knowledge and social structures.

At the local level, concepts such as memories, values, and knowledge play a particularly important role, as these have often grown over many years or decades in the local context, thus holding communities together (1). By preserving artifacts associated with this time, such as buildings, furniture, or other products, the social fabric is thus also preserved. If these objects worthy of preservation are adapted to our present time through handwork, for example, new layers of time can emerge, which in turn are expressions of the people who created them. Moreover, in collaborative work, social interaction is promoted in a very low-threshold way and can, for example, give rise to long-term neighbourhoods and increase the ability to cooperate (2). Moreover, experiencing the importance of one’s own role can lead to an increased willingness to participate in socio-political processes in the local or national context (3).

The global level is not so different from the local – whether watching an experienced craftsman on site or via video tutorial – the difference is small. Digital planning and manufacturing processes are particularly wellsuited to an exchange of knowledge and experience via the Internet, and accordingly this exchange is part of everyday life for many DIY communities. The enormous potential when people make an effort to develop other people around the world cannot be overestimated. Parallels can also be found to the local level with regard to democratic processes – globally, shared information about the shaping of our (surrounding) world also empowers many people to participate in this very shaping. In this way, bottom-up processes can be set in motion that lead to greater independence for people (4).

However, it should also be pointed out that – as always in the digital space – the possibilities for manipulation and abuse are manifold. Adequate selection processes are required to filter out relevant and verified information. “With choice comes responsibility” (5).

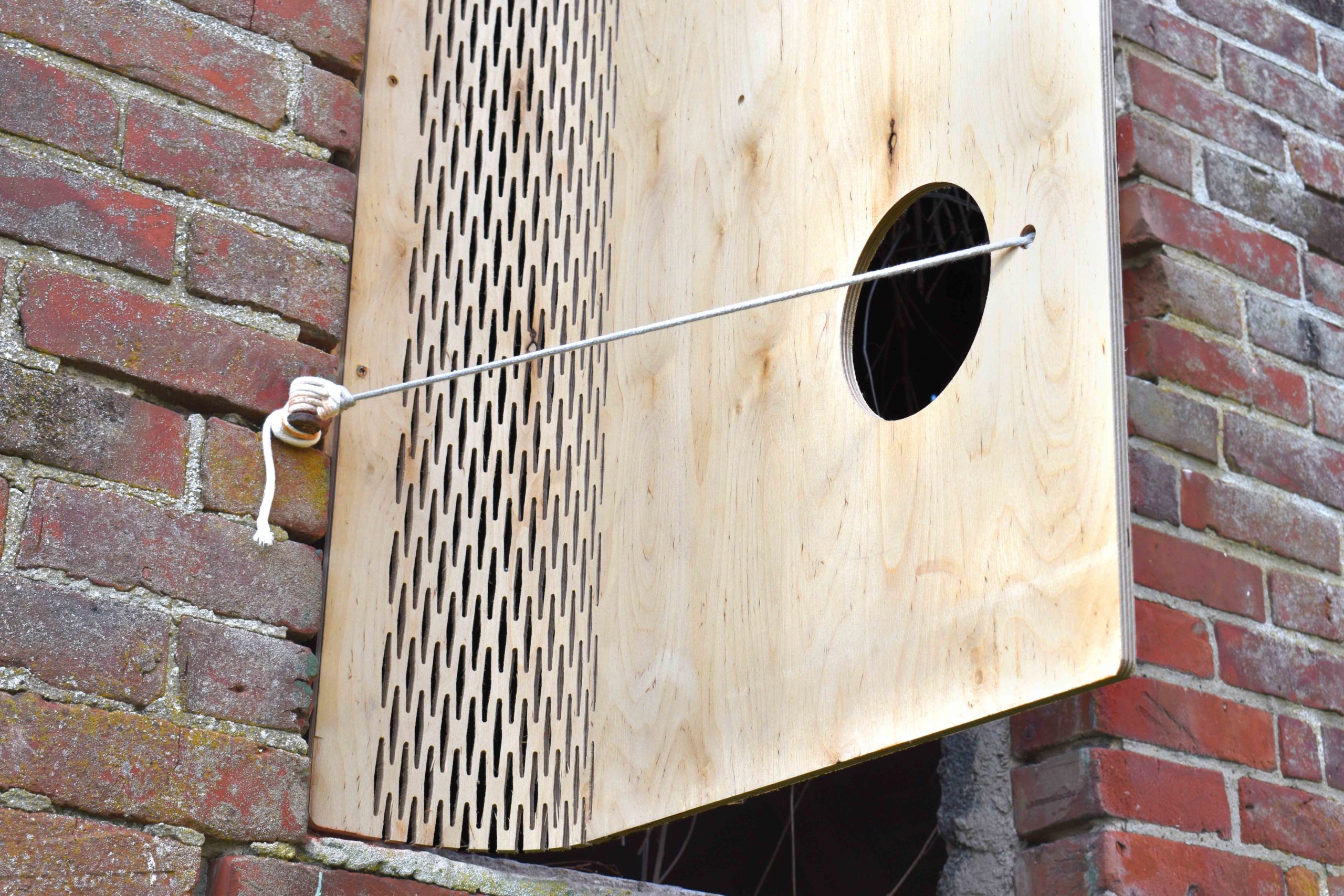

The practical project of this thesis links the local and global levels by adapting globally provided planning data to produce an open-source classic (Valoví Chair by Denis Fuzii, Opendesk) to local conditions in such a way that an unused relic of an earlier time – an old concrete wall – is given new life. In addition to minimizing time and risk during planning and fabrication with the M2, it was possible to create a contextually unique piece.

(1) Szypulski, Anja: Gemeinsam bauen, gemeinsam Wohnen: Wohneigentumsbildung durch Selbsthilfe. 1. Auflage. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften / GWV Fachverlage, 2008.

(2) Sennett, Richard: Zusammenarbeit. Was unsere Gesellschaft zusammenhält. Berlin: Hanser, 2012.

(3) Gravagnuolo, Antonia; Serena, Micheletti; Bosone, Martina: A Participatory Approach for “Circular” Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage. Building a Heritage Community in Salerno, Italy. Basel: MDPI, 2021. [Online] https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094812.

(4) Atkinson, Paul: Do It Yourself: Democracy and Design. In: Journal of Design History. Volume 19, Issue 1. 2006. S.1-10.

(5) Rijken, Dick: Design Literacy: Organizing Self-Organization. In: Open Design Now. Why Design Cannot Remain Exclusive. Hrsg. von Bas van Abel. Amsterdam: BIS Publishers, 2011. S. 152-159.

These 4 - Architectural practice

The core of the thesis formulated here is that the participation of new actors will subject the construction and production process to a strong change. This also affects planners and experts, since the participation of laypersons in design processes of all kinds brings new perspectives, motivations and desires into these processes. On the one hand, this makes experiments and innovations possible, but on the other hand, it also makes a repositioning of the experts necessary. By making the process of creation more open, dynamic, changeable, recursive, and iterative (1), there is no longer the one elite author or professional group of authors that determines the fate of the others, but it is more of a collaborative work. As a result, the professional planner will rarely design a specific product, but rather the processes necessary to create that product. A form of “meta-design” will emerge that creates user-friendly environments in which laypeople can design (2). Professionals will then become more like consultants, community managers, or even teachers. In addition, a new form of education will become necessary that teaches digital manufacturing from elementary school through university (3). ConvivialCNC also defines itself as such a meta-design.

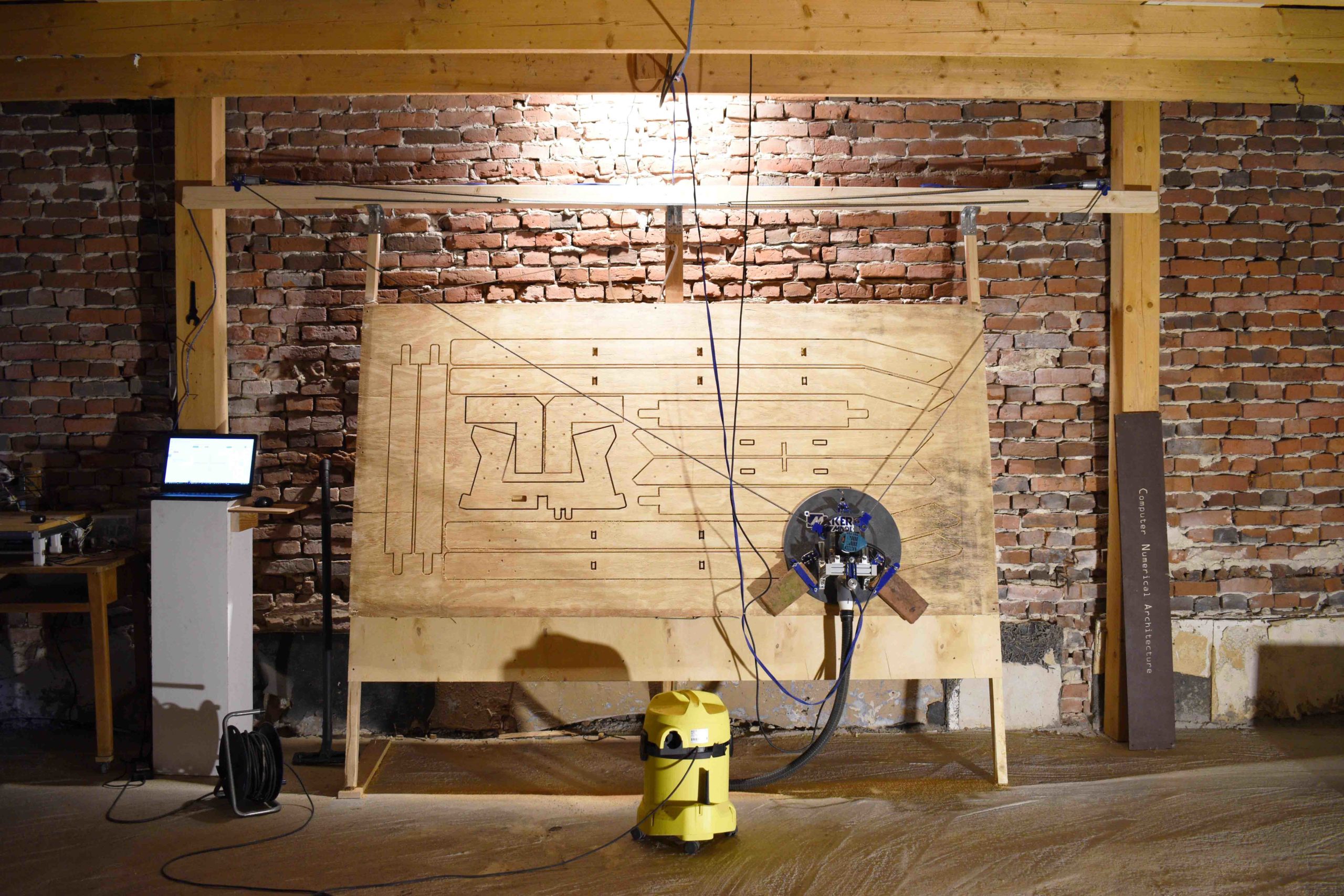

The practical project for this thesis attempts to illustrate these disruptive processes by questioning one of the most fundamental elements of architecture with the help of globally accessible information: the door. A door leaf is developed that is made of 100% wood and does not require any metal parts such as fittings, hinges or the like.

(1) Drexler, Hans: Open Architecture: Nachhaltiger Holzbau mit System. Berlin: JOVIS Verlag, 2021. [Online] https://doi.org/10.1515/9783868599572.

(2) De Mul, Jos: Redesigning Design. In: Open Design Now. Why Design Cannot Remain Exclusive. Hrsg. von Bas van Abel. Amsterdam: BIS Publishers, 2011. S. 34-39

(3) Kennedy, Gabrielle: Joris Laarman´s Experiments with Open Source Design. In: Open Design Now. Why Design Cannot Remain Exclusive. Hrsg. von Bas van Abel. Amsterdam: BIS Publishers, 2011. S. 118-127

CONCLUSION - CONVIVIAL TOOLS

Overall, it can be said that CNA has great potential to replace at least part of today’s established (construction) economy and to make global production more sustainable in ecological, economic and sociocultural terms. Whether this is more of a challenge, partial substitution or replacement will have to be seen in the processual dialogue with the business community.

Nevertheless, it became clear that CNA also entails limitations. Chief among these are overburdening the individual with complex tasks and lack of expertise; lack of quantitative studies on environmental sustainability; and increasing complexity and responsibility by introducing a comparatively sophisticated technology into the world of amateurs.

The low-tech CNC technology used for this work, as well as others, is a real step in this direction – but the practical phases have also shown that a great willingness to learn, a high investment of time, a certain tolerance for frustration, and also manual dexterity may be necessary to get started in such a mode of production. It thus becomes clear that the socioecological transformation can only succeed if a professionally guided cooperative development of design literacy is accompanied by a high level of accessibility to the relevant technology and the right personal mindset on the part of the actors.

In the context of socio-ecological transformation and the described need to cooperatively overcome barriers associated with CNA, the concept of convivial society is very interesting. The idea is based on Ivan Illich’s 1973 book Tools for Conviviality and has not lost its relevance today. Conviviality is based on establishing Homo Cooperans, i.e. cooperating humans, as a counter-image to Homo Economicus, i.e. rationally managing humans (1). A convivial society is characterized by a close relationship between people, but also between people and their environment (2). It is communicative, processual and unfinished (3).

In particular, the idea of convivial technology, which assumes that technology is not only developed by humans but always has an impact back on humans and thus deserves special attention, is crucial in the context of this work. The idea of convivial technology is precisely at the intersection of technology, ecology and sociology – as is the work presented here. For this reason, ultimately, ConvivialCNC is also developed against a background of conviviality.

Sources:

(1+2) Vetter, Andrea; Best, Benjamin: Konvivialiät und Degrowth. Zur Rolle von Technologie in der Gesellschaft. In: Konvivialismus. Eine Debatte. Hrsg. von Adloff , F. Heins, V.M.. Bielefeld: Transcript, 2015. S. 101-111

(3) Vetter, Andrea; 2016: Andrea Vetter: Kompass Konvivialität – Elevate Festival 2015. [Video] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nYrRlgWj5kw (20.08.2021).

Convivial CNC

With the ConvivialCNC, a project is developed that translates the theoretical findings into a mobile CNC milling unit as a conclusion of the thesis. ConvivialCNC is developed as a convivial technology that is characterized by, among other things, high accessibility and openness, with the goal of increasing the design literacy of actors and thus making socioecological transformation more likely. ConvivialCNC is a meta-design that spans a framework by which people can design. It opens up possibilities for people, challenges the status quo, is an avant-garde counter-design to a society in a mania of increase, a seed form for something new. ConvivialCNC can be temporary, move on, adapt. It is open, because it does not anticipate the type of use, its potential lies in the application by as many different people with diverse ideas as possible. Concrete information on how it is built and how it works can be found here.

FURTHER READING

.Agkathidis, Asterios: designing with digital tools. In: computational architecture. digital designing tools and manufacturing

techniques. Hrsg. von Asterios Agkathidis. Amsterdam: BIS Publishers, 2012. S. 6-9.

Aguilera, Alfredo; Davim , J. Paulo: Wood composites: materials, manufacturing, and engineering. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2017. [Online] https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110416084.

Apaydin, Veysel: Shared Knowledge, Shared Power. Engaging Local and Indigenous Heritage. Cham: Springer, 2018.

Atkinson, Paul: Orchestral Manoeuvres in Design. In: Open Design Now. Why Design Cannot Remain Exclusive. Hrsg. von Bas

van Abel. Amsterdam: BIS Publishers, 2011. S. 24-31.

Avital, Michel: The Generative Bedrock of Open Design. In: Open Design Now. Why Design Cannot Remain Exclusive. Hrsg. von Bas van Abel. Amsterdam: BIS Publishers, 2011. S. 48-59.

Brown, Roni: IDENTITY AND NARRATIVITY IN HOMES MADE BY AMATEURS. In: Home Cultures. Bd. 4, Nummer 3. 2007. S.261-285 [Online] https://doi.org/10.2752/174063107X247305.

Bürklin, Thorsten; Peterek, Michael; Reichardt, Jürgen: In Case we Want to Survive. A Plea for an Architecture of Responsibility. 2021. [Online] https://www.climatehub.online.

Buthke, Jan; Larsen, Niels Martin; Ostenfeld Pedersen, Simon; Bundgaard, Charlotte: Adaptive Reuse of Architectural Heritage. In: Impact: Design With All Senses: Proceedings of the Design Modelling Symposium. Hrsg. von Ramsgaard Thomsen, Mette; Weinzierl, Stefan; Burry, Jane; Gengnagel, Christoph; Baverel, Olivier. Cham: Springer, 2020. S. 59-68.

De Decker, Kris; 2014: How Sustainable is Digital Fabrication?. [Online] https://www.lowtechmagazine.com/2014/03/how-sustainable-is-digital-fabrication.html (14.08.2021).

De Silva, Dilantha; Perera, Kanchana: Barriers and Challenges of Adaptive Reuse of Buildings. Moratuwa: Department of Building Economics, University of Moratuwa, 2016. [Online] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319879628_Barriers_and_Challenges_of_Adaptive_Reuse_of_Buildings.

Facit, 11.08.2021: We‘re back! (on-site manufacturing). [Online] https://www.facit-homes.com/post/we-re-back-on-site-manufacturing (06.09.2021).

Fatorić, Sandra; Biesbroek, Robert: Adapting cultural heritage to climate change impacts in the Netherlands: barriers, interdependencies, and strategies for overcoming them. Delft: Delft University of Technology, 2020. [Online] https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02831-1.

Ferraro, Emilia; Reid, Louise: On sustainability and materiality. Homo faber, a new approach. In: Ecological Economics. 96. Jahrgang (2013-12-01). Hrsg. von Elsevier BV. Amsterdam: Elsevier B.V, 2013. S. 125-131 [Online] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.10.003.

Gasparotto, Silvia: Open Source, Collaboration, and Access: A Critical Analysis of „Openness“ in the Design Field. In: Design Issues. Bd. 35, Nummer 2. . Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2019. S.17-27 [Online] https://doi.org/10.1162/desi_a_00532.

Gauger, Ian: Adaptive Reuse as a Means for Socially Sustainable (Re)Development: How Reuse of Existing Buildings Can Help to Establish Community Identity and Foster Local Pride. Rochester: Rochester Institute of Technology, 2020.

Gershenfeld, Neil: How to Make Almost Anything: The Digital Fabrication Revolution. In: Foreign Aff airs. 91. Jahrgang, Heft 6. 2012. S. 43-57.

Ivan Illich: Tools for Conviviality, 1973.

Kloft, Harald: Digital Manufacturing and Sustainability. In: Digital manufacturing in design and architecture. Hrsg. von Asterios Agkathidis. Amsterdam: BIS Publishers, 2010. S. 130-133.

Kohtala, Cindy: Addressing sustainability in research on distributed production: an integrated literature review. In: Journal of Cleaner Production. 106. Jahrgang (2015-11-01). Hrsg. von Elsevier BV. Amsterdam: Elsevier B.V, 2015. S. 654-668 [Online] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.09.039.

Kuznetsov, Stacey; Paulos, Eric: Rise of the Expert Amateur: DIY Projects, Communities, and Cultures. In: NordiCHI 2010: Extending Boundaries – Proceedings of the 6th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction. ACM Press, 2010. S. 295-304. [Online] https://doi.org/10.1145/1868914.

Laitio, Tommi: From best Design to just Design. In: Open Design Now. Why Design Cannot Remain Exclusive. Hrsg. von Bas van Abel. Amsterdam: BIS Publishers, 2011. S. 190-199.

Maldini, Irene: Attachment, Durability and the Environmental Impact of Digital DIY. In: Design journal. 19. Jahrgang, Heft 1. Great Britain: Taylor & Francis, 2016. S. 141-157.

Priavolou, Christina; Niaros, Vasilis: Assessing the Openness and Conviviality of Open Source Technology: The Case of the WikiHouse. Basel: MDPI, 2019. [Online] https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174746.

Priavolou, Christina: The Emergence of Open Construction Systems: A Sustainable Paradigm in the Construction Sector?. In: Journal of Futures Studies. Bd. 23 (2). Taipei: Tamkang University, 2018. S.67-84 [Online] https://doi.org/10.6531/JFS.201812_23(2).0005.

Priavolou, Christina; Tsiouris, Nikiforos; Niaros, Vasilis; Kostakis, Vasilis: Towards Sustainable Construction Practices: How to Reinvigorate Vernacular Buildings in the Digital Era?. Basel: MDPI, 2021. [Online] https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings11070297.

Thackara, John: Into the Open. In: Open Design Now. Why Design Cannot Remain Exclusive. Hrsg. von Bas van Abel. Amsterdam: BIS Publishers, 2011. S. 44-45.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: The Paris Agreement. [Online] https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement (04.05.2021).

Unterfrauner, Elisabeth; Shao, Jing; Hofer, Margit; Fabian, Claudia M.: The environmental value and impact of the Maker movement – Insights from a cross‐case analysis of European maker initiatives. In: Business Strategy & the Environment (John Wiley & Sons, Inc). 28. Jahrgang (2019-12-01), Heft 8. 2019. S. 1518-

1533 [Online] https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2328.

van Hippel, Eric: Democratizing Innovation. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005.

Vetter, Andrea: The Matrix of Convivial Technology – Assessing technologies for degrowth. In: Journal of Cleaner Production. 197. Jahrgang (2018-10-01), Heft 2. Hrsg. von Elsevier Ltd, 2017. Amsterdam: Elsevier B.V, 2017. S. 1778-1786 [Online] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.02.195.

Vetter, Andrea: The Matrix of Convivial Technologies, 2017.

Vetter, Andrea: Konviviale Technik – Empirische Technikethik für eine Postwachstumsgesellschaft, 2022.